Newsletter Subscribe

Enter your email address below and subscribe to our newsletter

By Steven Saint

In 25 years, food riots will break out all over the world as the demand for food outpaces our ability to produce it – at least according to recent computer models run by the Global Sustainability Institute in Cambridge, U.K.

On the demand side, human population continues to rise. On the supply side, industrial agriculture is slowly depleting the soil quality of the planet.

Throw in climate change impacts to fresh water and declining reserves of cheap petroleum, and you’ve got the Collapse of 2040 looming a couple short decades away.

“We’ve maximized our productivity in agriculture and our consumption trends are speeding up,” says Global Sustainability Institute Director Aled Jones. “We’re putting more and more strain on the food system. About the year 2040, production won’t meet consumption going forward.”

Jones and his colleagues say there is still time for a course correction, but what changes need to be made now to avert the collision?

They say what permaculturists and the United Nations researchers have been saying for some time: build a resilient local-food system to replace the large dinosaur about to keel over.

“Smallholder farmers” could be catalysts for a “transformation of the way the world manages the supply of food and the environmental services that underpin agriculture in the first place,” said Achim Steiner of the UN Environment Program regarding a 2013 study by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre and the International Fund for Agricultural Development.

The paradigm shift indicated in these studies is moving away from a global system where wealthier regions help feed poorer ones to a system where each region can feed its own people.

The word “foodshed” has come to describe the area where food is produced and consumed. A local or regional foodshed has been defined in numerous ways (eg. within a 400-mile radius).

Generally, in the arid west, a foodshed is defined by its watershed. The Pikes Peak Region – El Paso County and the city of Colorado Springs – is in the Arkansas Valley watershed and Fountain Creek tributary.

The Local Food Working Group of the Green Cities Coalition organized an action-oriented, strategic assembly of local food leaders and enthusiasts in February called Pikes Peak Foodshed Forum II.

The question tackled by some 70 people at the forum was how to move our region away from almost complete reliance on the global food system to 10-25 percent self-reliance.

Several strategic themes emerged from the forum: train a body of local food ambassadors and leaders to build community around food access and knowledge; advocate for food policy priorities; develop a local food resource hub; and protect and enhance regional food production in the Arkansas Valley.

Food leaders are now developing tactical plans to achieve tangible goals. For example, we’d like to imagine El Paso County broken down into neighborhood-size chunks we’re calling “villages.” These villages would need to develop their own capacities to produce food.

One ready-made way to identify village-size areas is to map the region’s elementary school attendance boundaries. The school districts have already done the work of drawing lines to create neighborhoods of relatively equal size. Each village already has at least one institutional hub – a school. Many schools have parks, gardens and kitchens.

There are approximately 90 elementary schools in El Paso County. We are now looking for ambassadors or mentors willing to represent and serve their village in the cause of increasing food production and access.

These ambassadors will collaborate on a food-shift road show we can take to all the villages as part of a educational campaign around the importance of local food.

The PPJPC’s Sunrise Garden Project has been working all year with partners at the Hillside Community Center. The Hillside Village is an important pilot project, with a vision to turn what is now a food desert into a food hub. Food leaders will be planning the first of these traveling food forums at Hillside by the end of the year.

Another major development for the foodshed strategic priorities is the recent formation of a regional Food Policy Advisory Board. The seven-member board, sanctioned by both the county and city, has met twice and will be chaired by Local Food Working Group facilitator Megan Andreozzi.

The group also includes Lyn Harwell of Seeds Community Café, UCCS professor Nanna Meyer and Colorado Springs Urban Homesteaders organizer Monycka Snowbird. Sophie Javna is a non-voting student member representing the Colorado College Food Coalition.

The hope is that this advisory board will tackle land use, zoning, water, government procurement and any other policies that would expand the availability and access to locally produced food.

This is crucial to the second major priority identified at Pikes Peak Foodshed II.

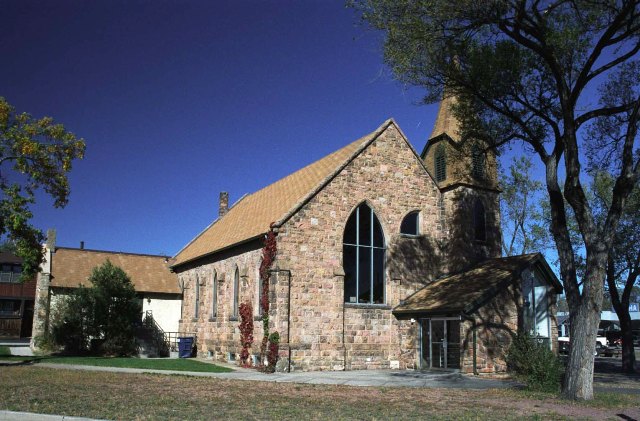

One project in need of city assistance (as well as funds) is the Colorado Springs Public Market. A vision is now emerging to purchase the former Payne Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church at 320 S. Weber St.

The triangular block bordered by Weber Street and Vermijo and Pueblo avenues could be the hub of a small public market district featuring locally produced food.

The hope of the Local Food Working Group is that the many efforts to localize the region’s food system can work harmoniously towards a different future than the one Cambridge researcher Jones compiled, complete with food riots and wars for water.

“Local production of food is incredibly important,” says Jones. “We can’t solve the problem with the same thinking that caused the problem.”

Steven Saint is the PPJPC associate director for media and was a co-founder of the Green Cities Coalition Local Food Working Group in 2009.